Mechanics of human embryo compaction - Nature

J. Firmin, N. Ecker, D. Rivet Danon, V. Barraud Lange, H. Turlier, C. Patrat, J-L. Maître, Nature 2024 (in press)

Read more: publisher - preprint

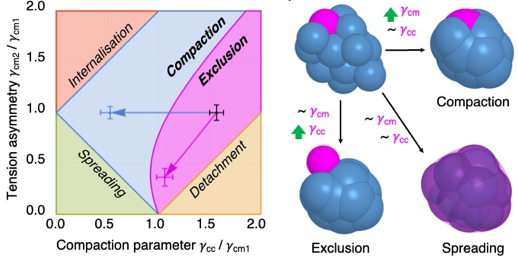

The shaping of human embryos begins with compaction, during which cells come into close contact1,2. Assisted reproductive technology studies indicate that human embryos fail compaction primarily because of defective adhesion3,4. On the basis of our current understanding of animal morphogenesis5,6, other morphogenetic engines, such as cell contractility, could be involved in shaping human embryos. However, the molecular, cellular and physical mechanisms driving human embryo morphogenesis remain uncharacterized. Using micropipette aspiration on human embryos donated to research, we have mapped cell surface tensions during compaction. This shows a fourfold increase of tension at the cell–medium interface whereas cell–cell contacts keep a steady tension. Therefore, increased tension at the cell–medium interface drives human embryo compaction, which is qualitatively similar to compaction in mouse embryos7. Further comparison between human and mouse shows qualitatively similar but quantitively different mechanical strategies, with human embryos being mechanically least efficient. Inhibition of cell contractility and cell–cell adhesion in human embryos shows that, whereas both cellular processes are required for compaction, only contractility controls the surface tensions responsible for compaction. Cell contractility and cell–cell adhesion exhibit distinct mechanical signatures when faulty. Analysing the mechanical signature of naturally failing embryos, we find evidence that non-compacting or partially compacting embryos containing excluded cells have defective contractility. Together, our study shows that an evolutionarily conserved increase in cell contractility is required to generate the forces driving the first morphogenetic movement shaping the human body.